-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

Inland

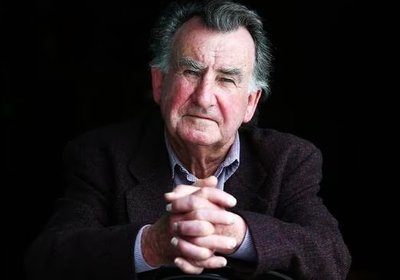

Gerald Murnane

And Other Stories, Jan 2024

As I read Inland, I think back to a conception of the poem that Osip Mandelstam and Paul Celan both shared, the latter adapting it from the former. That of the poem as a message in a bottle sent out in the hope a reader will find it washed up on a shoreline at some point in the future. Although the narrator (or implied author, a term Murnane uses elsewhere) of Inland claims to dislike the ‘idiot-sea’ and associates it with poetry, this image of writing as a message in a bottle chimes with his thoughts on how his writing could get sent out into the world:

. . . someone in future may find one of these pages drifting and may take it for a page of a book.

What’s more, the three-part image of poet-message-reader hinges on his most treasured preposition: ‘between’. The book, these pages, as he calls them, exists between the writer and the reader. He is conjuring the contents of the pages into being before his eyes and ours, though only we, reading in real time, know it has an end, whereas he, writing in real time, feels the infinite ahead:

While you read you are sure of coming to the end of the pages. But while I write I cannot be sure of coming to the end.

At times the writing in these pages seems to be directed to a specific reader, such as the woman editor he imagines awaiting his pages in the Calvin O. Dahlberg Institute of Prairie Studies. Towards the end of the book, the reader becomes a different woman he knew as a child, as the narrator tells us, this book started with a letter to her. The book attempts throughout to set up various ways for the narrator to approach his reader—real or imagined, with such ties forming and dissolving before our eyes. This writer-reader relationship is always foremost and a prerequisite for any writing to happen:

I could not think of words without a reader.

The word, for this writer, is dialogic and can only exist between the two. As he conjures up his desired reader, we, another kind of reader, must go along with him. At other times he suddenly addresses us, the general reader, dropping the previous set-up to announce:

Now, you still read and I still write but neither of us will trust the other.

He prepares us:

I am going to write for some time, reader, about myself standing in the garden . . .

Assures us:

I am far from having forgotten you, reader.

Plays with, or demands of, us:

But who, in any case, do you think I am?

Always reminding us of our connection with the book between us:

. . . since you are reading this page at this moment.

What fuels this book, powering it forward, is the writer’s seeking out of the other, the reader.

I am not concerned with defining this as a novel or non-fiction or otherwise. Elements of biography and fiction fleet across the pages like the thoughts that pass through our minds all day. Elsewhere Murnane has suggested that what he writes are essays, and with this he frees himself to wander over any imagined borderlines of genre. He plays with the possibilities of that thing in the middle as though with a Rubik’s cube, gliding from story to something else. He can hold all the sides of the thing in his mind: rather he can speak from several sides of it at a time. Simultaneity is a truth he draws us to.

Whatever it is, his is a kind of writing I greatly admire: one where the writer admits the reader behind the scenes. The scenes of what? Beyond the set-up of the monologic self directing itself to the blank page, beyond the simple accumulation of material, of ‘aboutness’. I sense this behind-the-scenes quality also in Clarice Lispector’s writing, in her addresses to the reader and her existential investigations. Writers who are a mystery to themselves are my favourite kind, occupied as they are with a study of self. In both writers I find a purity of writing, nothing superfluous, never narrative-driven, all is being laid bare. There is here a sense of the writer-narrator filtering, remembering, unfolding and conjuring material into being, going over it again and again.

What adds to this sense of a behind-the-scenes are Murnane’s references to the process and timing of writing these pages. He cuts through the pretence, gets behind the façade of writing, and brings the reader behind the scenes with him.

But what do we find there? Personal geography, whereby the self is established by places real and imagined.

Let me tell you, reader, what I consider you to be. [ . . .] Your body is a sign of you, perhaps: a sign marking the place where the true part of you begins.

All the places we have read of in books, he tells us, leave an impression on our selves. Whatever places we have seen or remember seeing or dreamed of seeing ‘appear on the map of the true part’ of us. The map of the places of our true selves. This map is not full:

All those empty spaces, reader, are our grasslands.

And in these grasslands are our possible selves. Here we have body, place, self, geography and potentiality all in one.

Instead of narrative there are passes over the same ground, with each pass yielding something new. For him, depth with layers and rootedness is king. Poetry is like the waves of the ‘idiot-sea’ while prose is ‘grassland movements’. How to understand this ‘idiot-sea’? In a book also published by And Other Stories, I read:

The transformations of the self are the business of the lyric poet.

This is a quote by Günter Eich in Lutz Seiler’s book of essays In Case of Loss. If I put these two things from different books read on the same day together, it gets me somewhere helpful. It gives me an insight into what I’ve been doing for the past thirty years and what Murnane isn’t doing here.

As a poet, I have been occupied with the nature of self in the lyric mode, exploring (swimming in?) the unknown. Murnane’s concern is not with the transformation of self. He is a writer of fixed geography and his task is to take in the layers that exist contemporaneously.

. . . the chief pleasure of my life, which is to see two places I had thought far apart lying in fact in one place—not simply adjoining one another but each appearing to enclose or even to embody the other.

and

I will match landscape with landscape.

The principle of multiplicity guides or inspires his central way of being:

I learned that no thing in the world is one thing; that each thing is two things at least, and probably more than two things. I learned to find a queer pleasure in staring at a thing and dreaming of how many things it might be.

He revels in the potential multiplicity of things. If he were a poet of the idiot-sea we would be talking about metaphor. But for him this is ridiculous. Metaphor. Why call one thing another, for him they can be both or more.

As he looks into complex layers where what could/would/might have been exists alongside the actual present, he conjures himself into imaginary situations to see what might happen there. Then he speaks as if these things were real, before suddenly snapping (us) out of it.

Most of all the narrator of Inland likes the moment of being about to write something and imagining himself in the place of another so that he can see things from a different angle. Here is a mode, a tense, a potentiality that inspires him. It brings the writer and reader together in the moment of something being written, and combines with his idea of multiplicity. Until a thing has been done, it exists in all its states of possibility.

I had been about to write what I have just written, but when I stood between my table and the window I thought for a moment what my reader would have thought if he had been reading the pages where I had read the words my reader. I had thought for a moment what a man would think if he saw himself clearly named on a page he was reading.

In Inland background is foreground. The narrator is concerned with location and direction, where the most prized, significant descriptors are the flanks of whatever lies between: all places are given as being located between two points, usually rivers. We the reader track and mirror his movements as he seeks out relationships of betweenness: tracing maps, seeking out pairs, mirrorings, signposts to follow. He starts with the ground, the place and puts a name to it. Indeed, he loves a good place name: the Great Divide, Climax, the Great Alfold, Ideal, Dog Ear, Oral. Disappointment Creek.

In one version of his future he imagines having studied the languages of specific places, the ‘soil-of-speech’, which gives rise to particular ways of speaking:

. . . I might have become a scientist of the depths of languages. I might have learned that a language grows from roots and soil just as grass grows. I might have followed the dialect of my native district down to its roots. I might have studied the soil and even the rock under the language of my homeland.

Gaining an insight into his own language, he dreams: ‘I would become at last a scientist of my own writing’—reclaiming that most treasured place from which he was taken as a child, his home.

Indeed, language is so intertwined with place that he finds his bearings not just by a language of place, but a language that is place:

When I hear the silence that comes between my own words sometimes, I think of prairies or plains—as though all my words are being spoken from grasslands. But whenever I hear the silence that comes between the first five and the last two of the seven words spoken to me by the girl from Bendigo, I think of depths.

The energy of potentiality that pulses through these pages stems ultimately from the unsolvable mystery of the other. He can never know the intention with which precious words were said to him via a go-between when he was twelve. As he meticulously picks over a girl’s declaration that she likes him ‘very much’, he lays out an analysis not of sentiment, but of language. As I read those pages I feel something shifting in my brain: I am slightly altered. I feel, not for a first time, but in a new way that language is real and shapes and creates and goes forth. And there is eternity, ongoing time: ‘an action that can never have been brought to an end’. And as such he manages to impart to us an immense sense of loss without using any emotive language. We suddenly find ourselves in a place where communication is happening.

And now we are in a sacred position:

The words I have just written are written as though to a go-between. But a man who writes on pages such as these can only have for his go-between his reader.

Towards the end he talks of a final mirroring. Each page between us is not a window, he realises, but a mirror. Perhaps then, I think, each reader completes Inland having read and looked into it. It becomes part of our individual geography: one that is moulded by the landscape of another’s mind. I read-watch in wonder as he seemingly conjures this book from behind-the-scenes: a place only he can go but only if he knows we are here to receive his reports from back there.

Caroline Clark has published three books: Saying Yes In Russian (Agenda Editions); Sovetica and Own Sweet Time, both with CB editions. She has recent work and a podcast interview on Fictionable. In 2026 Black Herald Press will publish What Lies Ahead and Other Essays. She lives in Lewes, England, and works as a community interpreter for Russian speakers. @cclarklewes.bsky.social