-

-

The Discerning Mollusk's Guide to Arts & Ideas

-

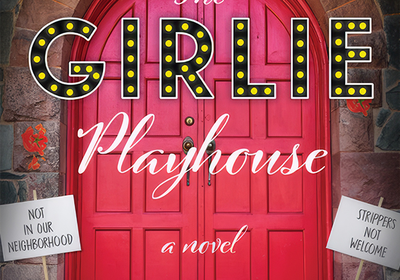

The Girlie Playhouse

V. N. Alexander

Heresy Press, Apr 2026

Follow your bliss, but don’t expect to be understood. Worse: you might be pilloried. Such are the stakes in V.N. Alexander’s latest novel, The Girlie Playhouse, a tale of exotic dancers who try to find a place in a world where they are met with incomprehension or bad faith.

The title refers to a cabaret where the narrator, Pixie, dances nude. The story centers on another dancer, Trixie, whose appearance and performances fascinate Pixie. She avows, “My entire life has been an expression of my peculiar love for girls with meretricious charms.”

The story opens with the cabaret under attack by outsiders who want to close it down. The Gideon Angels, a feminist group of Carrie Nationesque killjoys, inspire protests by “misguided, albeit well-meaning” student activists from the local university’s “Oppression Studies Department.”

Thus the battle lines are drawn. At first blush, the above description, putting apparently infantilized “girlies” with cheesy names on one side, and dour moral enforcers on the other, seems to promise a broad satire. And that is, in fact, one feature of the novel. At the same time, however, The Girlie Playhouse raises more complicated questions about performance and personal autonomy.

Alexander pushes back at received images of dance venues as merely tawdry or exploitive, grim places for desperate women with nowhere else to go. Pixie’s story is not devoid of risks—violence against women figures in the plot—but these characters assert agency. Pixie says that her method “is to complicate the issue rather than clarify,” which is a sentiment that implicitly reflects the author’s approach, too. The male gaze, she claims, can also serve her purposes: “while the breath of the men constantly threatens to extinguish, it actually feeds my flame.”

Exotic dancing, for Pixie, is not just a job, but a need. She’ll dance naked on her porch under the gaze of a blackbird on a maple tree because, for her, “Any pair of eyes will do.” This aspect of self announced itself early. She recollects being scolded by her auntie, when she was only six years old:

“Stop that prancing around like a little harlot, you gypsy girl. Where is your modesty?” [. . .]

I stamped my tiny foot and demanded, “What was I doing wrong?”

“It’s not what you’re doing. It’s what everyone’ll think.”

“I don’t care what they think.”

This pattern persists into her adult life, and is corroborated by her friend Trixie, in the context of Trixie’s relationship with her boyfriend Max. Max is a regular customer at the Girlie Playhouse. He recently won the lottery, thereby freeing him of financial worry. He’s hopelessly smitten with Trixie, and his good luck continues when Trixie returns his affections. What more could he want?

As it turns out, a lot more: namely, control. He challenges the need for Trixie to continue dancing.

“Don’t tell me you want to be a stripper. I thought it was just the money.”

Trixie looked at him with bitterness. “You’re not making sense.”

“You’re the one who’s not making sense. You don’t have to strip anymore.”

“I never had to before,” she said.

“What do you get, Trixie, what do you get out of being at a strip club that you couldn’t get dancing somewhere else?”

“I like it.”

The ensuing discussion, in which Pixie participates, addresses the question that hovers over much of the story. Why? Why does she like it? Max defensively poses the question in reference to another man:

“Why do you need to dance for him?”

“It’s not for him,” replied Trixie, groping for her point. “It’s at him.”

“Oh, I see at him. Well, that makes perfect sense.” Max laughed, tickled with the idea that her argument was weak. “Pixie, now you tell me, do you dance at or for your customers?”

I hesitated for a few minutes, biting my thumbnail, considering this delicate point.

“Through,” I said finally. “Through.”

This conversation does indeed complicate the issue. A reader could parse this as a sad testimony to how much the patriarchal gaze has colonized the female psyche, resulting in a socio-sexual “captive mind.” Or a reader can conclude that dancing through the gaze of others is an empowering move, surfing across a liminal space on a wave of desire. Or a reader, particularly a reader weary of theorizing, can conclude that our pleasures are polymorphous—yes indeed—so enough said. Sometimes a cigar is just a mirror ball.

I found these ambiguities interesting. Elsewhere, Pixie says up front: “there is a phenomenal pattern in the hazy chaos of events, one that cannot be explained entirely by psychological factors.”

In any event, realistic convention isn’t a priority here. When not dancing at the Girlie Playhouse, Pixie lives quietly by herself in a snug garden cottage, tending wildflowers. She leads a pastoral, fairy-tale life, where money isn’t an issue.

Sex, when it occurs (not that often) is also refracted. Alexander’s satirical strategy is to describe it with somewhat prim or florid language, the opposite of a striptease reveal. For instance, in a voyeuristic scene, Pixie watches Trixie as Max “resolutely possessed the coquette.”

For all its playfulness, the emotional core of the novel—its ideology, if you must—seems to be to a concern about the ills that arise when someone decides for someone else. I’ll avoid spoilers, but the novel is tenacious on that point. Full of surprises, The Girlie Playhouse subverts cliché. V.N. Alexander is a serious stylist who is not afraid to ruffle feathers.

Charles Holdefer lives in Brussels. His latest novel is Don’t Look at Me (Sagging Meniscus, 2022).